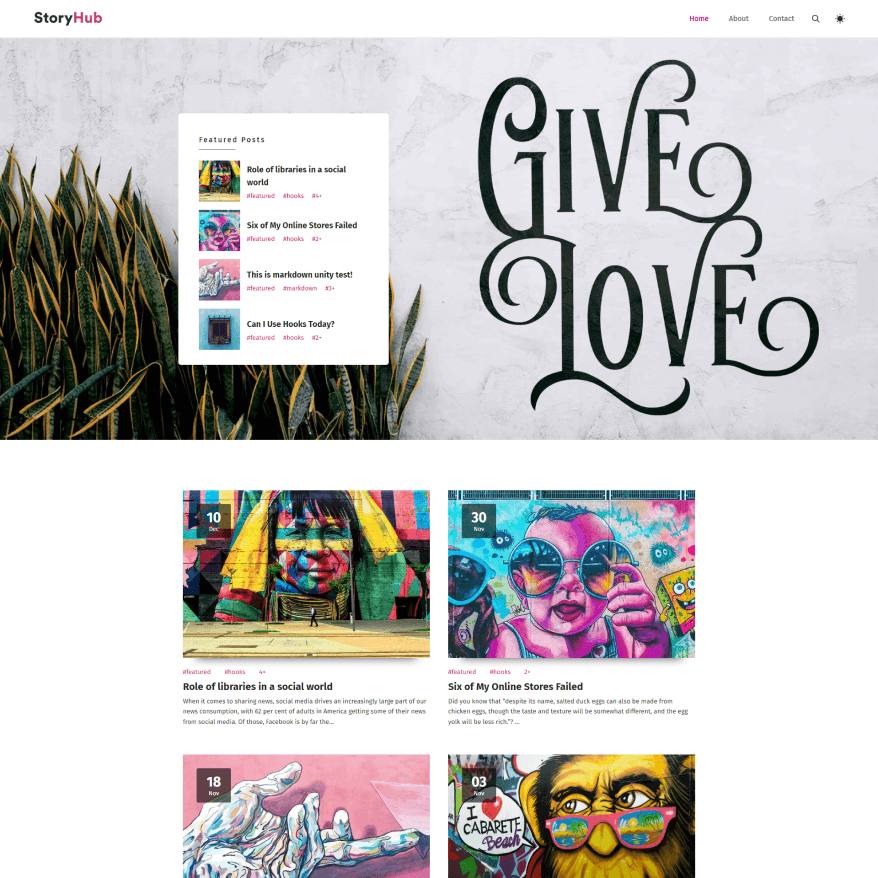

Given the discourse around this issue, it can be easy to either overestimate the scope of this problem, or discount solving it as irrelevant to the libraries’ mission. Recent studies have shown that the scale and impact of fake news is less significant than much of the initial reporting would suggest. While many people get their news from social media, they do not always consider it their primary source of information (Illing, 2017). Moreover, the basic trends that drive fake news include an increasingly partisan media culture that predates social media (Mittell, 2016). Perhaps most importantly, there is evidence to suggest that when people are presented with “inoculating” messages beforehand, for example information about the scientific consensus or information about the general strategies used in misinformation campaigns, it made a significant positive difference in how they interpreted subsequent information even when it taps into their preexisting identities (Cook et al., 2017; van der Linden et al., 2017). That is to say, the rise of fake news, while a serious problem, does not signal a general inability for people to identify and process facts or that there are no strategies that can effectively counteract these tendencies. Rather it signals something important about how emotions and identities, particularly when exploited by technology platforms, can influence our understanding of new information. Moreover, outside of those emotionally driven, identity-based incentives, there is less of a reason for people to use technology to generate purposefully misleading information.

Yet, just as the technology companies’ first impulse was to ignore their newfound responsibilities as media companies, libraries too must begin to re-think their obligations in light of the ways people are actually using information. Already, both librarians and other stakeholders are working to reconfigure information literacy instruction. As we look to the future, the definition of purposefully fake news used at the outset of this column may be less relevant, as new variants of these themes complicate the picture. There are many factors that can lead to patrons being misled (both purposefully and accidently) by information sources. Efforts to update information literacy are beyond the scope of this column, but it will be an ongoing effort that will continue to evolve as the profession grapples with new research – both research into how people interpret information as well as how various actors attempt to deceive them. As poll numbers demonstrate, these trends are occurring even as people’s trust in institutions diminishes. While trust in libraries remains relatively high, the overall trend is worrisome for institutions of all kinds.

What a deep understanding of technology can do for this effort is highlight the systemic forces that allow misinformation to spread. This includes the incentives behind socially shared news, which are, in turn, built on human-created algorithms to harness basic human impulses. Across the board, people are, and always have been, bad at recognizing and accepting information that goes against their preconceptions. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt suggests, in many arenas, we may believe we are rational scientists, coldly evaluating information, but in reality, we operate more like press secretaries, spinning available facts to confirm our preexisting beliefs (Haidt, 2013). It is, therefore, valuable and important work to provide updated information literacy practices to library patrons. It has the potential to change their lives and help create a better society. Yet it is likely not sufficient in and of itself, simply because of the limited scale, and, perhaps, more importantly, the inability to reach people who most need this assistance.

Yeah, I didn’t either.